The Life of

Theodore Ruggles Timby

© 2022 Christine

M. Wands

all rights reserved

Theodore Ruggles Timby, 1819-1909

Meridian, New York, was certainly home to smart and imaginative individuals, but there was one village resident that surpassed all the others in the volume of his patents, and in his ability to be at the center of controversy for his entire life.

Theodore Timby may have been one of the most interesting people in Meridian’s history. He had a larger-than-life personality and an inventive genius that kept his name in the public eye from the age of twenty-one until his death at the age of ninety. His tactics concerning the Tempest Insurance Company showed us another side to his inventiveness. He indulged in shameless self-promotion, evaded censure when it was well-deserved, and failed at multiple attempts to get money (that he may or may not have deserved) from the US government.

Timby

was born in Dover, Dutchess County, in 1819[1]

to George Washington Timby, Sr., and Sarah Johnson Timby. The Timby family was

peripatetic; their six children were born in at least five separate places

around upstate New York as George moved from farm to farm as a laborer. One son

was born in Massachusetts. Before coming to Cayuga County, the family lived in

Chenango, Steuben, and Tompkins Counties.

Theodore

was probably in Meridian (then still called Cato Four Corners) by 1831. His

father, and his older brother Augustus R Timby, were in the area and were both

baptized that year in the village Baptist Church. Theodore was baptized there

eight years later. Two other siblings, Benjamin, and Emaline, were baptized

there in 1851. [2]

In

1844, Timby married Charlotte Ware (Wears), who was born in Madison County. Her

father, Newman Ware, a cooper, moved to the Meridian area with his family by

1835, when he became a member of the Baptist Church. Newman was from

Middlefield, Massachusetts, from whence many Meridianites emigrated in the 19th

century.[3]

Theodore

and Charlotte had four children: Theodore, Cecelia, Judson, and Mary. Both sons

died young. In addition to Augustus, two other siblings of Theodore were in the

area: Benjamin and Emeline. There were also baptized in the Baptist Church.[4]

The

Cato Citizen reported that he was remembered “by old settlers” as being

“very suave and of striking appearance,” and that he introduced climbing roses

to the community. He was also said to have planted currant cuttings “bottom

side up so they grew like trees instead of bushes.” [5]

As

an inventor, Theodore Ruggles Timby started early, designing a floating dry

dock while he was just seventeen. While living in Meridian, he was granted at

least seven patents: an apparatus for raising sunken vessels, a stone dressing

machine, a manner of connecting the body with the runners of sleighs, two

improvements on water wheels, a removable handle for sad-irons, and a method

for changing the diameter of a water wheel. (A list of his inventions is at the

end of this document.)

Timby

was a force to be reckoned in the community. He was raising a family, paying

his slip tax at the Baptist Church, getting involved in politics, and dreaming

up new inventions at the same time he was declaring himself a farmer in census

records. He built at least one house. It still stands on the west side of the

Bonta Bridge Road, the third house south of the main street.

Timby’s home in

Meridian (from the collection of CIViC Heritage, Cato, NY)

Timby’s home in

2022 (author’s collection)

Before

he left the village under a cloud in 1855, he served in 1853 as the Inspector

of Elections for the Town of Cato[6]

and was one of nine delegates from Cayuga County to the Whig Senatorial

Convention, 24th District.[7]

In

January 1843, Timby had filed a caveat with the US Patent Office for a

“revolving tower to be used on land or water.”

A caveat, now no longer used, was an official notice of intent to patent

an invention, was in force for a year after its filing, and could be renewed.

The document included a description of the invention and drawings but was not an

actual patent claim. That he filed the caveat, which was not renewed, but never

the patent, would cause controversy for decades to come, and eventually cost

him dearly.

Between

1851 and 1855, he appears to have taken a break from inventing things. In 1853,

he had become the Secretary of, and agent for, the newly created Tempest

Insurance Company of Meridian. This turned out be a turning point in his life

in Meridian.

The

Tempest Insurance Company was created in early 1853 by a group of Meridian

businessmen. Many other groups throughout New York State created similar

companies following the passage of New York’s general insurance law in 1849.

An

insurance journal reported, “During the years from 1849 to 1853, about sixty

different mutual fire insurance companies came into existence…infesting the

land like frogs in Egypt…for nearly eighteen months they apparently waxed fat,

and everything went on swimmingly; but as soon as losses began to happen the defects

of the system showed themselves.”[8]

At

that time in American history, the economy was booming. The California Gold

Rush expanded the supply of money. Railroads were transporting substantial

numbers of settlers westward and making huge profits while doing so. Credit was

readily available, and the economy was rapidly expanding.[9]

People

in rural America operated on credit during those years, and did not often have

cash. The capital of the Tempest Insurance Company consisted entirely of

promissory notes. Even the premiums paid by policyholders were promissory notes.[10] When

they began doing business in 1853, their capital consisted of $100,000[11],

all basically IOUs. By the next year, they claimed that their capital had grown

to $250,000.[12]

One of many advertisements in the Genesee Farmer throughout 1854.

In

their second year of business, they instituted a public relations effort by

donating a $3,000 policy to William H. Seward, then a U.S. Senator from New

York. The policy covered Seward’s home in Auburn, and was referred to as a

“compliment,” since “such a manifestation from an Incorporated Institution is

rare, inasmuch as all Incorporated Companies have always been considered as

soulless.”

In

the letter to Seward that accompanied the policy, T.R. Timby, as Secretary of

the firm, stated,

The

Directors of the Company are, many of them, personally known to you. The

Company is perfectly reliable, as they are established on a reliable basis; and

we take none but first-class risks. You will please accept of this Policy from

us, as a remuneration in part, for the many favors received from your generous

hand. Be assured, sir, should you meet with a loss, our portion of the same

would be paid, while the walls were smoking, should you notify us in time. [13]

All

this self-promotion appears to have worked; the company did a lot of business

throughout New York State, and even had clients as far away as Michigan, whence

many central New Yorkers had moved during that period. Records in the

collection of the CIVIC Heritage Museum in Cato, New York, tell of a busy company

that issued hundreds of insurance policies.

Collection of documents and policies of

The Tempest Insurance Company in the collection of the CIVIC Heritage Museum,

Cato, NY

In

the company’s third year, the State of New York was eager to examine the books,

as they did for all such companies chartered in New York. By the end of 1854,

the company had not made the required reports to the state.[14]

This effort was to ensure

that the company was still solvent and conducting business in an orderly manner.

The effort did not go well.

William

Barnes, Superintendent of the state’s Insurance Department, sent James

Henderson, Special Commissioner, to do the inspection. He arrived in Meridian

on May 21, 1855. His report began:

In

compliance with my commission to investigate the affairs of the Tempest

Insurance Company, Meridian, I went there on Monday, the 21st… for

that purpose. The Secretary, T.R. Timby, was absent. I then went two miles to

the residence of the President, Parsons P. Meacham and laid before him my

business. We then found the secretary’s clerk, [E.H.] Northrup, and proceeded

to the office. There seemed to be evident confusion at once, as they were

almost entirely ignorant of the concerns of the Company. When I called for the

capital, assets, etc. they said they were locked up and Mr. Timby had the keys,

and the only fact that I could establish, that the number of policies issued

from January 1st to 18th, 1855, inclusive was 124.

Mr.

Meacham told Mr. Henderson that the company was planning to re-organize, and

implied that to issue a report at the time “would make no difference.” Henderson realized that he was getting

nowhere, and said he would be back on Wednesday. On Tuesday, the clerk, Mr.

Northrup, sent him a note that Timby was not going to be home on Wednesday, so

coming then would be fruitless. (It was later discovered that Northrup had met

Timby in Auburn on Tuesday, and that Timby then headed for Albany.) Henderson

said that he would be back in Meridian on Friday, and that he would tolerate no

further delay.

He

arrived in the village on Friday, only to learn that Timby had gone to

Rochester “for the purpose of getting up a new company.” He headed back home to

Weedsport, but Mr. Meacham followed him and asked him, as a “special favor to

wait until next Monday, 28th, before reporting; said that Timby

would probably succeed at Rochester, and whether he did or not, something would

be done, and he would see me on Monday.”

Monday

came with no word from anyone at the company. On Tuesday, Henderson went to

Conquest to take a statement from H.F. Hale, formerly the clerk of the company,

and Rev. Goss, a local minister, who was formerly a director of the company.

Henderson’s

report said that Hale and Goss “hope…that now Timby will succeed in getting up

the new Company, which will assume the assets and liabilities of the old

Company, and thus spare them the disgrace that they feel is settling upon

them.”

Hale’s

statement indicated that while he had worked for the company for about two

years, he had resigned in January, feeling that he “was doing wrong to continue

in the service of a Company whose business was carried on so illegally and

unjustly.” He told Henderson that the

January report had stated the premium notes on which policies had been issued

amounted to $100,000, but that they were not more than $800 or $900. The same

report had indicated that there was $20,000 on deposit in the Cayuga County

Bank, but Hale said that such a sum had never existed. When Timby returned from

Auburn, Hale asked him if Henderson had managed to get the information he

sought. Timby replied, “I guess not much. I had the key in my pocket.” He told

Hale he did manage to get $20,000 from the bank. Hale’s final comment was “I

consider the whole matter unsound and dishonorable.”

Goss

indicated that “he was grossly imposed upon by Timby and deceived” and that he

was “satisfied that a majority of the board of directors, were, and have been

all the time, led along by Timby, and relied upon what he said, more than upon

their own knowledge or judgment.”

Henderson’s

report concluded: “I know some of the board to be men of high standing, and

feel that they have been caught in bad company. I have endeavored to give you

in detail what I have done, or could do, trusting I may be honorably discharged

from a very unpleasant duty,”[15]

That

spelled doom for the company.

Timby

eventually resigned from the company, but not until December.

Timby’s Letter of

Resignation from The Tempest Insurance Company

from the Meacham family papers collection at the CIVIC Heritage Museum, Cato,

New York

Timby

had left town by the fall of 1855[16], moving to Syracuse, where he engaged

in another company with a similar name.[17]

From

an Auburn newspaper:

Tempest Insurance Company

The

following letter is in reply to one from F.A. Rew, Esq., making inquiries with

regard to the above named company. We understand that quite a number of persons

in this vicinity have taken policies of insurance in that concern:

Comptroller’s

Office, Albany, March 6, 1856

F.A.

Rew, Esq.:

Sir:

The Tempest Ins. Co., formerly at Meridian, in Cayuga Co., was examined under

the direction of the late Comptroller Cook, and the result of such examination proves it to have been under

the management of a smart Secretary, by name Timby. It is bogus,

or in other words, good for nothing. There is no company of that name in

any part of the State Lawfully authorized to do business.

Respectfully,

A.W. Lee, Ins. Clerk[18]

Eventually,

the company did reorganize as “The Tempest Insurance Association,” in December

1855, as a “joint partnership in which…the entire individual responsibility of

the Partners is pledged for its liabilities.”

When

Timby decamped, in the fall of 1855, he was heavily in debt. Possessions left

behind were taken by the county sheriff.[19] Where he went is not documented, but he and

his family boarded in Syracuse for as long as a year. A Mrs. Charles L.

Chandler remembered meeting Timby, his wife, and their two children when she

and her husband were boarding at the same place. She remembered the date as

being 1850. She called Timby “a gentleman of the old school, brilliant and

quite able to put out the line of literary work of which he is the author.” [20] Her memory was certainly faulty as to the

date, since Timby had remained in Meridian until 1855, according to US and New

York State censuses, newspaper accounts, and other records.[21],

[22]

Timby

filed his next two patent applications, for a mercury barometer and a traveling

casket, from Medina, in Orleans County, in 1857 and 1858. During that time,

many family members, including his parents, his brother Benjamin, and sister,

Emaline Schuyler, were all living with 15-20 miles of Medina, so that is the

likely explanation for his moving there. The next evidence for Timby’s location

came in 1862, when he was applying for patents from Worcester, Massachusetts.

It is unknown why or when he moved there.

His

inventiveness continued. His next patent was granted in August 1863, for a

solar time-globe. By then, he was living in an upscale neighborhood (in a brick

house valued at $10,000)[23]

in Saratoga Springs, New York, where his occupation was listed in censuses and

city directories as “inventor.” He lived there until his wife Charlotte died,

probably in late 1870. That year’s census, early in the year, showed only Charlotte

living in Saratoga Springs with her daughters and her son-in-law, Frank H.

Walcott, a druggist. Theodore’s name showed up in Manhattan in that census,

living in a boarding house with his occupation listed as “paper mfg.” One can

conjecture that after his wife died and his daughter married, he moved on alone.

Where his daughter Mary was remains a mystery.

His

life in New York City was only a temporary thing. By the end of 1870, he was

applying for patents from Tarrytown, New York. It is likely that is when his

daughter Clementina Cecelia Timby Walcott moved to Nyack, New York, directly

across the Hudson River from Tarrytown. So, Timby is again moving near family.

In 1879, patent applications, when he was sixty years old, were coming from

Nyack.

Six

years later, he was living in a boarding house on F Street NW, three blocks

from the White House in Washington, DC. He filed a dozen applications while

living there. Some newspaper accounts indicated his whereabouts as Chicago in

1893[24]

and Philadelphia in 1898.[25]

His

final destination was Brooklyn, New York. That was where he filed his final

seven patents beginning around 1904. A 1900 newspaper account says that Timby was

a guest of Mrs. Virginia Chandler Titcomb,[26]

and he appears to have remained her guest until his death in 1909.

After

Timby’s death, the Brooklyn (NY) Times Union told of their meeting:

Timby

came to live in Brooklyn a little more than ten years ago. It was through a

meeting he had had with Lady Alice Carolyn Carvell in the Hotel Astor. She

spoke to her friend, Mrs. Virginia Chandler Titcomb…regarding the man and how

he had been cheated out of the credit for his invention. Mrs. Titcomb,

well-known and brilliant artist, looked him up and found him walking the

streets, and hungry. She took him and after learning his story began to work to

get him recognition from the Government.

She

spent all her money, and she was a rich woman when she found him, in this

endeavor. She even mortgaged her property from which indebtedness she was

relieved by friends. She sold even her most prized paintings to aid him.[27]

Mrs.

Titcomb was an interesting character in her own right. She was a member of the

Hudson River school of artists and painted in oils. One of her paintings was of

the Civil War battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac. A

firebrand in the cause of women’s rights, she was president of the National

Industrial Union, which gave women employment, and provided classes in the fine

arts, music, and the domestic arts.[28]

A political activist and friend of Henry Ward Beecher [29],

she served as president of the Women’s Republican Union League in Brooklyn,[30]

and fought for women’s suffrage, even speaking at the national convention of

the National Council of Women on the same panel as Susan B. Anthony.[31]

Her role as founder and president of the Patriotic League of the Revolution[32]

gave her the podium that she used to advocate for Theodore Timby from the time

of his arrival in Brooklyn until his death.

Virginia Chandler

Titcomb,

from Women in Music and Law, by Florence E.C. Sutro, 1895

In

addition to dreaming up new inventions, Timby tried his hand at writing. In

1888 he founded a magazine, the “Congress Magazine,” in Washington DC. He published four books, including “Bridging

the Skies” (1883), “Beyond,” (1889), “Stellar Worlds and other

Didactic Literature” (1896), and “Lighted Lore for Gentle Folk,” (1902). Some

of these are still available, in both in original and reprint editions. The

“Lighted Lore” is a collection of uplifting aphorisms and poetry. His classical

references therein indicate that the “common school education”[33]

attributed to him must have been excellent – or he managed to educate himself

throughout his lifetime. One of the items is of especial interest, considering

his activities as Secretary of the Tempest Insurance Company:

Bridging the Law.

Bridging

an honest and lawful route to final success, even in this world, is a failure

and a crime. Many have made the experiment, and as many efforts have failed.

There is no success minus self-respect.[34]

Timby

received praise for his inventive genius and was awarded three honorary

degrees: the A.M. degree from Madison University in 1866, the Sc.D. degree by

the University of Wooster (now the College of Wooster in Ohio) in 1882, and the

LL.D. degree from the University of Iowa in 1890.

The

reason for Mrs. Titcomb’s ascending the podium to shout out the praises of

Theodore Timby was his most important invention, a “revolving tower to be used

on land or water.”

The

whole thing began in 1841. Timby was 21 years old and living in Cato Four

Corners (In some of his narratives about the visit, he said he was nineteen.).[35]

He visited New York City for the first time

and took a ferry across the harbor to Jersey City to catch a train for

Washington, DC, his ultimate destination. In one of many interviews about that

trip, he told this story about the day the idea came to him and the subsequent

events. This story was repeated, nearly word for word, in multiple interviews

over the years:

It

was a clear bright day, and as the ferry glided smoothly over the water I stood

at the bow and scanned every passing object with minute scrutiny.

At

last we came in sight of old Castle Williams. Somehow the round brick structure

fascinated me strangely. Even after the queer old fortress, pierced for three

tiers of guns, had been left far behind me my thoughts were still upon it.

Suddenly it occurred to me that if the structure were so built as to revolve

upon a vertical center, the guns pointing arbitrarily up stream could be used

at will down stream or at any point of the compass at which an enemy might

chance to present itself. Of course, in order to do this it would have to be of

iron construction.

This

idea clung to me so persistently that the next day but one after my arrival in

Washington I made a rude pencil sketch of the revolving turret, illustrating

but little more than the bare principle.” [36]

By

this time I was full of boyish enthusiasm over what I dreamed might prove to be

a great invention. At first I was at a loss what to do. Then came the thought

that I would enlist the interest and influence of the great and powerful

members of Congress.

The

fame of John C. Calhoun, then in the United States Senate [and former Secretary

of War in the cabinet of James Monroe], had made his name familiar in every

country town, and guided by some freak or fancy, I determined to seek an

audience with the eloquent southern statesman.

I…went

to the..Senate, with a heart beating like a triphammer. Almost to my surprise,

the Senator at once responded in person and gave me an attentive and patient

hearing, carefully examining my crude sketch… He not only acknowledged the

originality and possible importance, but asked me if I could not produce

something better in the way of an illustration than the rude sketch…

When

I went down those stairs - well - I walked on air! The following day I went to

Baltimore and hunted up an ivory turner. He agreed to make me a model, which he

did by aid of the drawing and personal suggestions as I stood by him and

watched my conception take material form under his skillful chisels.”

Castle Williams on Governor’s

Island in New York Harbor

(ChrisRuvolo, CC BY-SA 4.0

<https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>,

via Wikimedia Commonsused under license)

He

returned to Washington with the model and presented it for Calhoun’s

examination.

After

a close scrutiny of the little model, which I have always carefully kept and

still have, he sent for Senator William G. Preston of South Carolina. Then they

introduced me to other Senators of their acquaintance. Without an exception

they all approved of the probable practicality and importance of my invention

and suggested that I submit it to the chief of ordinance and chief of

engineers.” [37]

Timby

did so, presenting his idea and the model to George Bumford, Second Chief of

ordnance for the US Army Ordnance Corps, as well to the chief engineer, who both

appear to have thought it was an excellent idea.

Later on, Timby’s

model also was presented to a committee from the army and the navy, who

determined the cost made it impractical. [38]

In

1842, he decided that a larger model, in iron, was necessary. The model was

built in the Phoenix Foundry on East Water Street in Syracuse, next to the Erie

Canal,[39]

at a cost of $5,000 (nearly $160,000 in 2021 dollars).

This

was to be an expensive endeavor, so he developed a partnership with three men

to build it: a Mr. Beard of Fayetteville, Mr. Pitcher of Syracuse, and a Mr.

Stiles of Baldwinsville. The men who did the work were George Herrick

(superintendent under Timby’s direction), Samuel Stapely, Alfred Dunk, a Mr.

Poole, Mr., Duel, Charles Herrick, and Richard Dudgeon. Joel C. Northrup, a

fellow inventor from Syracuse, remembered the building of the model and its

later exhibition in New York City:

The

machine was built upon a platform about seven feet square. On it was a circular

track on which the turret rested and it was equipped with segments of cog gear

that were connected with cog pinions on shafts in the floor of the platform and

were driven by two small engines. This turret was made of boiler plate, and was

about seven feet in diameter. It had a narrow deck on which the cannon were

placed. Of guns there were a number and they were discharged each in their

turn.

These

cannon were of bronze metal, in fact both the guns and the carriage. The guns

were about six inches long and the wheels were three inches in diameter. There

was a center part in the platform, which passed through the hub at the spider

which was connected with the segment rear at the base of the turret. The

turning of the turret was like the turning of the swing bridge in Salina

Street, except that it was turned by an engine.

Mr.

Stiles procured a platform car and the machine was loaded onto it at the shop

door. It was taken to New York and placed on the balcony of the City Hall on

exhibition. George Herrick went with it as engineer.

“The

Franklin Institute was in progress that week, and I went down to exhibit a

press which I had built there on my patent and which entered in the name of

Wheeler & Young, the builders.

“Mr.

Herrick got me to assist him in the exhibit at the City Hall on the day that

President Tyler was escorted through the city on his way to Boston to celebrate

the Bunker Hill monument.”[40]

In

June of 1843, the exhibition of the model was described as “a new instrument of

warfare, or rather an old instrument on a new principle…a fort containing one

hundred guns, in four rows…of twenty-five guns each… The whole arrangement was

pronounced by several military men...present to be perfect so far as this experiment

was concerned; should the plan succeed on an extended scale, it would be one of

the most tremendous and effective engines of defense ever invented.”[41]

This description doesn’t sound like the

model described by Mr. Northrup, but perhaps the writer also looked at

drawings, or was just exaggerating.

Another

viewer of the model, displayed at the corner of Greenwich and Liberty Streets

in New York, declared that “in no other way can so great a number of guns be

brought to bear upon an object in so short a time.”[42]

In

addition to presenting the idea to the US government, Timby shopped his idea

internationally. Caleb Cushing, US Minister to China for a few months in 1844,

presented the concept to the Chinese government (although Timby remembered it

as happening in 1843), and later, in 1856, Timby himself went to France and the

revolving turret was shown to Napoleon III,[43]

returning to New York on the steamer Fulton from Le Havre on July 17,

1856, empty handed, less than a year after leaving Meridian in the autumn of

1855. In 1857, he applied for a new passport, saying “my old one was dated May

10, 1856 & is about extinct by hard usage.” [44]

About

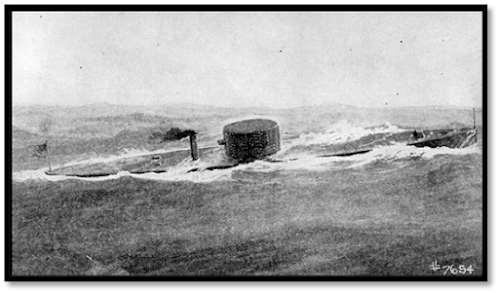

five years after Timby left Meridian, the Civil War began, and a year into the

war, the Battle of Hampton Roads took place between the Ironclad

Massachusetts-built Merrimac (renamed the Virginia by the

Confederacy) and the Union’s ironclad, the Monitor. Neither won this

battle, but the Monitor’s innovative design helped it hold its ground

against the Merrimac. The Monitor later sank off Cape Hatteras in

a gale. (Its wreck was found in 1973, and the gun turret was salvaged in 2002.)[45]

The

revolving turret was the Monitor’s distinguishing feature. John

Ericsson, the Swedish engineer, designed the ship, and he claimed credit for

the entire ship. It was a major innovation in war vessels. The Monitor’s appearance

initially generated laughter. It was called a “cheesebox on a raft” and

“Ericsson’s folly,” but that strange new look gave it an advantage. Since most

of the ship was at or below the water line, with only its turret in view, it was

not much of a target for other ships’ guns.

Plans of the Monitor. (Public Domain)

Timby

had continued to work on the revolving turret idea since filing his caveat in

1843. He must have been aghast when the Monitor was built with just such

a turret. Months after the battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac

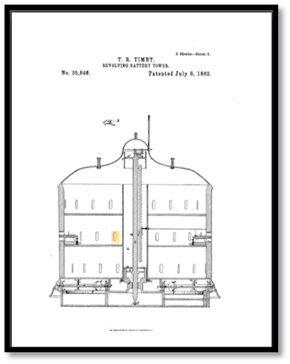

at Hampton Roads in March 1862, in July and September, he finally filed three patents

concerning the revolving turret idea.

Improvement in

Revolving Battery-Towers, July 1862, US Patent 35846

Improvement in

Discharging Guns By Electricity, July 1862, US Patent 35847

Improvement in

Revolving Battery-Towers, September 1862, US Patent 36593

Swedish

engineer John Ericsson directed the building of the Monitor with his

partners, C.S. Bushnell, John A. Griswold, and John F. Winslow, under contract

to the U.S. government. The contract read that if they would build an “Ironclad

Shot Proof Steam Battery” in one hundred days they would be paid $275,000

(about $8.5 million in today’s dollars). Ericsson’s motivation was clear when

he stated to Thomas F. Rowland, who owned the shipyard where the ship was to be

built, “You want money. I want fame. You can do the mechanical work on this

vessel in your shipyard, but it is my conception, and it must be understood

that it was built here in my parlor.”[46]

Ericsson’s conviction of his superior skills as an engineer and ship designer,

and the lack of any credit for the turret’s invention being given to Timby was

the beginning of a controversy that continued for the next half century.

John Ericsson,

1803-1889

(Public Domain)

Several

companies participated in the construction of the ship, including manufacturers

of iron, engines, lumber, paint, boilers, anchor, propellor, and so forth. It

was built at the Continental Ironworks, at Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York.[47]

The Monitor

at sea. (Public Domain)

The

ship was built as promised. Timby heard of the ship’s design and approached the

partners, telling them that the primary design of the ship was his own. “In

1862, I entered into a written agreement with the contractors and builders of

the original Monitor… for the use of my patents covering the revolving

turret for which they paid me $5,000 [$135,797 in 2021 dollars] as a royalty on

each turret constructed by them.”[48]

Most accounts say that he was paid for three such turrets.

Photo of the Monitor,

featuring Timby’s revolving gun turret. Photo from the National Archives.

In

1885, John F. Winslow supported Timby’s claim in a letter to Timby about “the

two-gun turret invented and patented by you and first used on the original Monitor,

built in 1862, under the supervision of Captain John Ericsson, engineer.”[49]

Nevertheless,

Ericsson continued to receive praise for the ship that changed naval warfare

forever. His supporters has remained strong, as a statue was built in 1903 to

honor his achievements at the Battery in New York City.[50]

Another memorial, authorized by the U.S. Congress in 1916, was dedicated in

1926. It is in Washington, DC near to the Lincoln Memorial.[51]

There have been three warships in the US Navy honoring Ericsson, as well as a

replenishment oiler.[52]

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, January 1863.

Meanwhile,

others were in Timby’s camp and doing whatever they could to give him the

credit they thought he deserved. Less than a year after the Monitor and Merrimac

fired on one another, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine January 1863 edition

featured an article entitled, “The Revolving Tower and Its Inventor.” The

article praised the turret, saying “a new and powerful element has been

introduced into naval warfare.” It went

on to say that “the inventor of the Revolving Tower, as we shall show from

unimpeachable documentary evidence, is Theodore R. Timby, an American citizen,

a native of the State of New York.”

The

article tells the story of the “mere boy” who came up with the idea, that he

filed a caveat with the Patent Office for “a revolving metallic tower, and for

a revolving tower for a floating battery to be propelled by steam.” It went one

to say that “this document thus placed on official record, shows beyond all

possibility of cavil that more than twenty years ago Mr. Timby had not only

conceived the general idea of a revolving gun-tower, but had brought it into

practical form, and laid public legal claim to his invention – a claim which

has never been abandoned or legally contested.”

Timby’s

reaction to the beginning of the Civil War was to create yet another model of

his turret, and he exhibited it to the governors of Rhode Island and Maine, to

the heads of federal departments, foreign ministers, and the Army and the Navy.[53] But, as we have seen, these efforts led

nowhere, and he eventually had to plead with the Monitor’s contractors

for some little recompense for the use of his invention.

Broadside

Championing Timby’s Cause, 1842

(Courtesy Aaron Noble, New York State Museum)

Timby’s

inventiveness continued. He designed a wide variety of items, but later

returned to turrets, both on land and sea. In the 1880’s, he filed more than

fifteen patents for ideas relating to turrets and defensive installations. Other

patents concerned ore processing, coffee roasting, aging wines and liquors, and

he also returned to water wheels, which related to earlier inventions made when

he was still in Cato Four Corners.

One

patent during those years was for a heating, ventilating, and cooling system.

Timby formed a company in 1889: The National Heating and Ventilating Company.

It began with a capital of $3 million. Former Surgeon-General William Alexander

Hammond was president, and Timby was second vice president. The company, using

the “Timby System” could provide heating services to an entire town from one plant.[54]

Advertisements

for the company touted the system’s merits: the system “cannot but be

regarded as one of the greatest inventions of modern times…It heats in winter,

cools in summer, thoroughly ventilates at all times, and deodorizes, fumigates,

and disinfects when required so to do…The system has been in successful

operation for nearly a year, winter and summer, in the Lawrence Building, 615

and 617 14th Street, Washington, DC”[55] There appears to be no further record of the

company after 1893.

In

1890, the New York State Legislature passed a resolution asking Congress to

give Timby national recognition for his invention.[56]

Timby

himself never stopped trying to get official recognition for his revolving

turret. In 1898, General John H. Ketcham, a Congressman from Dutchess County,

New York, presented a bill to Congress asking for an appropriation of $500,000

“as compensation for services rendered the government through the invention of

the revolving turret for warships and harbor defenses.”[57]

The

next year, Timby’s turret was one of the exhibits in the “vast museum” of the

Patent Office in Washington. “One of the most attractive of them all is the

model of the turret. We have been accustomed, all our lives, to believe that

Captain John Ericsson invented the turret for the celebrated Monitor,

which revolutionized naval warfare… But the fact is that Mr. Theodore R. Timby,

then a young man, in 1841, invented and patented the turret which made the Monitor

successful and gave Ericsson undying fame.”[58]

Another

bill went before Congress in 1900, “for the relief of Theodore Ruggles Timby,”

introduced by Congressman Bingham. It was referred to the Committee on Claims.[59]

Others

became enmeshed in the effort. A group of women in Brooklyn who were members of

the “Patriotic League of the Revolution,” gathered in 1900 “to correct an

error… which is taught in the schools and academies throughout the country, and

which has wrought a great injustice towards a benefactor and an American

citizen.” Timby’s benefactor, Mrs. Virginia Chandler Titcomb began the League

in 1887. The group planned to urge the US Senate to grant Timby credit.[60] In addition, the group planned to author a

book concerning the history of Timby and his turret, to be introduced into

schools to “correct the omission in school histories.” The State Superintendent

of Schools Skinner promised to assist in the effort.[61]

The

League presented a memorial to Congress in 1902 requesting recognition of Timby

for his invention. The memorial told the tale of the young man in New York

harbor, his invention after seeing Castle Williams on Governor’s Island, and

the meager $5,000 royalty paid to him. The memorial stated that “it was thus to

Theodore R. Timby, the American, and not to John Ericsson, the Swede, that the

defeat of the Merrimac and the revolution of naval warfare were due.”[62]

Portrait originally

published in the January 1902, edition of Successful American magazine.

Original caption: “THEODORE R. TIMBY, M.A., S.D., LL.S., Inventor of the

Revolving Gun Turret, now a Resident of Brooklyn, N, Y.”

Timby

continued to press his case. In 1904, the New York Times said of Timby,

“There is no fighter like an old fighter, especially when his fight is made in

the courts or ‘agin’ the Government.” Timby was filing with the US Court of

Claims, still upset that besides the royalties paid for the Monitor, he

has received nothing for the use of his turret, nor for his 1862 patent of the

device that fired guns with electricity. He stated that Ericsson did not apply

for a patent for the Monitor’s turret, and that he was paid royalties

for it. That was proof, he said, that Ericsson believed Timby’s caveat to be

good. He was hoping for “a settlement soon,”[63]

Timby’s

request before the Court of Claims:

Be

it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of

America in Congress assembled, That there is hereby appropriated, out of any

money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated, the sum of three hundred

thousand dollars as compensation of Theodore R. Timby for the use of his

invention and the infringement of said patent upon revolving turrets, and the

sum of two hundred thousand dollars for the compensation of said Timby for the

use of his invention and the infringement of his patent for the sighting and

firing of guns by electricity, which said sum shall be in each case in full

satisfaction of all claims for such use and infringement and that for the

relinquishment of all right to claim any further compensation for the use of

the same by the United States.

The

claim, filed in December 1906, stated that the government built fifty-five

ironclad vessels using sixty-eight turrets of Timby’s design during the Civil

War and that the government also adopted and used his invention using

electricity to discharge heavy guns. He claimed that he received no

compensation for such use.

The

efforts continued, but the Court of Claims was not on Timby’s side. The Court

reasoned that since Timby “did not keep the caveat alive,” that the Monitor

was constructed according to Ericsson’s plans, and that Timby had nothing to do

with the ship’s construction. Additionally, the Court said that the “principle

of a revolving turret was not a new idea when Timby filed his caveat, but that

the principle of revolving towers or batteries

to be used in battle has long been known, and such towers or batteries

were in use centuries since, and even before the invention of gunpowder…Guns

were fired by electricity at least one hundred and fourteen years before Mr.

Timby took out his patent.” So, in December 1907, the Court denied the claim.[64]

So

that was that for Mr. Timby. He died two years later at the age of ninety in

Mrs. Titcomb’s home in Brooklyn. His funeral was held there, with his coffin

covered with an American flag, with a card that said, “From friends who know

Timby-Turret-Truth and who will make it known to the world.” [65]

He

left behind “an invalid daughter and a disabled granddaughter wholly without

support.”[66]

It is unknown what happened to that daughter, presumably Mary Timby, and her

child. Mrs. Titcomb was credited with having “saved his daughter and

granddaughter from pauperism,”[67]

“having found that he had a daughter and a granddaughter living in want and she

took her in also; she sacrificed all her property.” [68]

His

death did not stop the controversy. Twelve days after his obituary appeared in

the New York Times, The New York Sun reported on a meeting of

“The Captain John Ericsson Memorial Society of Swedish Engineers,” at which

Professor William Hovgaard of MIT delivered a paper. Hovgaard did not pull any

punches. His paper tended “to disprove all of Timby’s claims except that did

conceive of the idea of a freak turret.”

Hovgaard stated “The design, if such it could be called was amateurish

and was nothing but an adaptation to guns of the revolving tower used in

ancient and medieval warfare…Ericsson had been acquainted with the old idea of

revolving turrets and had often speculated on its application to ship guns.” He

asserted that Ericsson had presented the idea of a low-decked ship with a

revolving tower to Napoleon III in 1854.[69]

In

Sweden, Ericsson is still revered. The Mosaic Ballroom in Stockholm City Hall,

covered in millions of gold mosaic tiles, features designs commemorating events

in Swedish history, and honoring Swedish heroes. One such design features

Ericsson, with an Eagle, and the initials “U.S.” above him.

Stockholm City

Hall, the Mosaic Ballroom, and Ericsson’s image

(author’s collection)

At

the time of Ericsson’s and Timby’s pilgrimages to France, Napoleon III was

establishing a modern French navy, with steam-powered armored ships. A

revolving turret would have been useful, but the emperor was not interested.

Syracuse,

which had long attempted to claim Timby as their own, even though he only had

his model built there, took up Timby’s cause in 1910. Prominent Syracusans were

“gathering evidence...which proves Syracuse man [sic] originated Revolving

Turret.” A committee of New York state residents were working for Timby’s

recognition, as well as “liquidating the accumulated obligations of Mr.

Timby…and…have provided suitable temporary burial for his body.”[70]

One of those committee members, W.B. Cogswell, was incensed that a U.S. battleship

carried John Ericsson’s body back to Sweden and felt that such honors belonged

to Timby instead.[71]

Mrs.

Titcomb’s Patriotic League continued the fight. They called for a mass meeting

to remove Timby’s body from his Brooklyn grave and arrange for a burial with

honors in Washington, DC. The announced that that they had found documents that

proved Timby’s claim.[72]

The

news of the search for documents reached Iowa, where Martin Van Buren, a former

resident of Meridian and one of the original founding members of the Tempest

Insurance Company, had settled. Van Buren’s daughter, Mrs. George Porter,

remembered that Mr. Timby had visited her father several times in Iowa, most

recently in 1870, and had given him some drawings relating to the revolving

turret. Mr. Porter stated “Mr. Timby and Mr. Van Buren were well acquainted

with each other when both resided in the east, and when Mr. Van Buren came

west, he was still interested in the inventor’s work, and gave him assistance.

Just how Mr. Van Buren came to be in possession of the old drawings I do not

know, unless they were sent to him, and were never called for again.” The

drawings showed “the working of the revolving turret, on both a ship and for

coast defence [sic].”[73]

The

movement to gain recognition for Timby also included raising funds to buy back

Mrs. Titcomb’s home in Brooklyn, which she had lost in her efforts to support

Timby. “We shall give back to the woman who cared for him in his last years the

home she lost in so doing.”[74]

Timby’s

supporters began to clamor for his body to be transported to Washington on a

U.S. battleship,[75]

but the Acting Secretary of the Navy disapproved the idea, which had been

presented to Congress.[76] Winthrop felt that providing a naval vessel

for such purposes would be tantamount to endorsing Timby’s claims of being the

inventor of the turret and that such claims had not been proved. Several members

of Congress were ready to continue the fight [77],

but the fight was in vain.[78]

Those

who fought to have Timby’s body moved to Washington were eventually successful,

although there were no naval ships involved. Ceremonies were held at the

Battery in New York in October 1911, where the body lay in state close to

Ericsson’s statue. A Dock Department boat carried his remains around Castle

Williams, and speakers declared “that honor was due both to Timby and Ericsson”

and that “there is glory enough for both.” One speaker, the poet Will Carleton,

was not quite so even-handed: “The fact remains that the Monitor was never

rebuilt for any length of time, bur the revolving turret has been used ever

since in divers [sic] parts of the world.”[79]

Upon

its arrival in Washington on 13 October 1909 a memorial service was held at the

First Congregational Church, where General Nelson Miles and officers of the

Army and the Navy were speakers. The coffin was draped in American flags. It

was buried the next day.[80]

Timby’s

body now rests in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, DC alongside his wife,

Charlotte, and sons Judson and Theodore.[81]

During

his lifetime, Timby was always ready to talk about his life and his inventions.

He often bragged about the important men he had known in his lifetime, claiming

that such men as William H. Seward, Millard Fillmore, Jefferson Davis, Henry

Clay, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln, Commodore Vanderbilt, and General Grant,

among others, had been close personal friends. Indeed, they may have met, but

no records appear to indicate that there were any strong friendships.[82]

One

man who never met him, but heard about him from Timby’s childhood friends, was

Gilbert Purdy. He was the oldest member of the Navy, 71 years old and in charge

of the hold of the USS Olympia. Such an achievement garnered him some

recognition by the press, and he reminisced with reporters in 1899. Some of his

facts were not totally accurate, but his characterization of Timby was

interesting.

I

was born back of Poughkeepsie, in Unionvale. Perhaps you didn’t know it, but

Theodore Timby, a farm laborer’s son from Dover, the town next to mine,

invented the Monitor turret. He patented it in 1841, but they said it would

cost too much to build it and it lay there in the patent office until Ericsson

saw it. I asked about Timby when I got back from the war, and they told me he

was the biggest lunkhead that was ever in a schoolhouse. [83]

Timby

was certainly not a lunkhead, but that farm boy grew up to be the most inventive

and most famous Meridianite.

[1] Depending on the source, Timby was

born in 1816, 1820, 1922, or 1823. Census records disagree, as do Timby’s own

accounts.

[2] Meacham, Anna May, The Baptist

Church at Meridian New York, 1810-1988: The Survival of a Rural Church, Havens,

William H., editor, Salem, MA: Higginson Books, printers, 2006.

[3] Massachusetts Births and

Christenings, 1639-1915, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FCV5-HYW

: 5 January 2021), Newman Wears, 1787.

[4] Meacham, Anna May, Ibid.

[5] Cato (NY) Citizen, 20

January 1927.

[6] Auburn (NY) Cayuga Chief,

25 December 1853.

[7] Auburn (NY) Journal, 19

October 1853.

[8] Dana, William, editor, The

Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review, Volume 46th, New

York: William B. Dana, publisher, 1862.

[9] “Panic of 1857,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panic_of_1857, accessed 3 October 2021.

[10] Meacham, Anna, quoted in “Local

Business History Outlined Before Cato Rotary Club Meeting,” Weedsport (NY)

Cayuga Chief and Chronicle, 5 December 1968.

[11] Barnes, William, New York

Insurance Reports, Volume 3, 1899.

[12] Undated Advertisements, Niagara

Falls (NY) Gazette, 1854.

[13] “Substantial Compliment,” Albany

(NY) Evening Herald, undated issue, 1853.

[14] Barnes, William, New York

Insurance Reports, Volume 2, 1860.

[15] Barnes, William, Ibid.

[16] Barber, Oliver L., Counsellor at Law,

“Clute vs. Fitch” Reports of Cases in Law and Equity Determined in the

Supreme Court of the State of New York, Vol. XXV, Albany (NY): W.C. Little

& Co., Law Booksellers, 1858.

[17] “Theodore

Timby, of Cato, Was Noted for Many Early Inventions”, Cato Citizen, 8 March

1962.

[18] “Insurance Companies,” Auburn

(NY) Weekly Journal, 9 April 1956.

[19] Reports of Cases in Law and Equity

determined in the Supreme Court of the State of New York, Clute v. Fitch, p.

407.

[20] “Moving Turret Invented Here,” Syracuse

Post-Standard, 10 May 1909.

[21] United States Census, Town of

Cato, New York 24 July 1850.

[22] New York State Census, Town of

Cato, New York, 7 June 1855.

[23] 1865 New York Census,

Saratoga Springs, New York, 9 June 1865.

[24] Postville (IA), Graphic, 21

December 1893.

[25] Hermitage (MO) Gazette, 1

June 1898.

[26] “Timby’s Friends Claim He Invented

Monitor, Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, 24 June 1900.

[27] “Timby’s Body to Go to

Washington,” Brooklyn (NY) Times Union, 1 September 1911.

[28] “National Industrial Union. The

Summer Branch Established at Asbury Park,” The Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, 7

July 1895.

[29] “Genius at Home,” Brooklyn (NY)

Daily Eagle, 15 July 1894.

[30] “Gold Vase for Mrs. McKinley,” Brooklyn

(NY) Daily Eagle, 17 November 1896.

[31] “Women’s Work – The National

Council Enters the Second Week in Washington,” The Pensacola (FL) News, 26

February 1895.

[32] “In the State Departments,”

Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, 9 April 1894.

[33] Meacham, Anna May, “Theodore

Timby, of Cato, Was Noted for Many Early Inventions,” Cato (NY) Citizen, 8

March 1962.

[34] Timby, Theodore Ruggles, LL.D., Lighted

Lore for Gentle Folk, New York: Morningside Publishing Co., 1902.

[35] “Invented the Turret – Theodore R.

Timby, Now and Old Man, Tells How He Hit Upon It,” Washington (DC) Evening

Star, 23 December 1893.

[36] “The Blue and The Gray,” Defiance

(OH) Republican Express, 8 March, 1894.

[37] “Invented the Turret,” Washington

(DC) Evening Star, 23 December 1893.

[38] “Local Inventor Forgotten Designer

of Ship Credited with Saving Union,” Syracuse (NY) Post-Standard, 27

December 1954.

[39] “In Honor of Timby,” Syracuse

Herald, 19 April 1911.

[40] Recollections of Joel C Northrup,

in “Invented by Dr. Timby,” Syracuse Herald, 21 May 1909.

[41] “Revolving Steam Battery,” New

York Herald, 7 June 1843.

[42] “A Novel Battery,” New York

Evening Post, 7 June 1843.

[43] “Our Sea Coast,” Watertown (NY)

Herald, 5 March 1887.

[44] United States Passport

Applications, 1795-1905, Roll 65, vol 140141, 1957 Sep-Oct., familysearch.org.

accessed 22 October 2021.

[45]

“Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimack,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-the-Monitor-and-Merrimack

, accessed 2 October 2021.

[46] Church, William C., The Life of

John Ericsson, 2 vols., New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890.

[47] Thompson, Stephen, The

Construction of the U.S.S. Monitor, New York: Page Publishing, 2019.

[48] “Navy, Covington,” Cincinnati

(OH) Commercial Tribune, 21 March 1909.

[49] Untitled article, Syracuse (NY)

Sunday Herald, 17 March 1889.

[50] “The Battery,” NYC Parks, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/battery-park/monuments/454, accessed 1 November 2021.

[51] “John Ericsson Memorial,” National

Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/nama/planyourvisit/john-ericsson-memorial.htm, accessed 1 November 2021.

[52] :YSS Ericsson,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Ericsson, accessed 30 March 2022.

[53] “The Revolving Tower and Its

Inventor,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, No. CLII, Vol. XXVI, January

1863.

[54] “The National Heating and

Ventilating Company,” The Rockland (NY) County Journal, 20 April 1889.

[55] National Popular Review, an

Illustrated Journal of Preventive Medicine, several issues, 1893.

[56] “To Honor Dr. Timby,” Washington

(DC) Post, 15 July 1910.

[57] “Seen and Heard in Many Places,” The

Philadelphia (PA) Times, 13 June 1898.

[58] “Washington Letter,” Rome (NY)

Semi-Weekly Citizen, 4 September 1889.

[59] Journal of the House of

Representatives of the United States, Washington, DC: United States

Printing Office, 1900.

[60] “Women Take Up His Case,” Brooklyn

(NY) Citizen, 24 June 1900; “Concerning Monitor Turret,” Brooklyn (NY)

Daily Eagle, 1 July 1900.

[61] “Women Writing a Book,” New

York Times, 8 July 1900.

[62] “Inventor of Monitor Turret,”

New York Sun, undated issue, 1902.

[63] “For 40 Years He Has Pressed His

Claim, New York Times, 25 April 1904.

[64] “60th Congress, First

Session – Findings in Case of Theodore R. Timby.” Document 126, 19

December 1907.

[65] “Heap Honors on Timby Bier –

Floral Turret Shows Friends’ Faith in Inventor’s Claim,” The Brooklyn (NY)

Daily Eagle, 13 November 1909.

[66] “Late Honors Paid to Inventor

Timby,” New York Times, 3 October 1911.

[67] “Row Over Monitor’s Inventor

Assumes Munchausen Proportions,” Jackson (MS) Daily News, 16 March 1911.

[68] “Movement to Honor Theodore

Ruggles Timby,” The Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, 7 April 1911.

[69] “Three Story Timby Turret,” New

York Sun, 24 November 1909.

[70] “W.B. Cogswell to Lead Fight for

Dr. Timby,” Syracuse (NY) Post-Standard, 21 January 1910.

[71] “Timby, Inventor of the Turret,” Syracuse

(NY) Post-Standard, 22 February 1911.

[72] “American, Not Ericsson,” Tipton

(IN) Daily Tribune, 11 February 1911.

[73] “Original Drawings of Inventor

Found,” Muscatine (IA) Journal, 11 February 1911.

[74] Movement to Honor Theodore Ruggles

Timby,” The Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, 7 April 1911.

[75] “From Potter’s Field to Fame,” Wichita

(KS) Beacon, 27 February 1911.

[76] “Disapproves Proposition,” The

San Antonio (TX) Light¸ 14 August 1911.

[77] “Demand a Warship,” The

Washington (DC) Post, 14 August 1911.

[78] “No Warship to Carry Body of Dr.

Timby,” Syracuse (NY) Herald, 26 August 1911.

[79] “Full Honor is Paid T.R. Timby’s

Memory,” Brooklyn (NY) Daily Eagle, 13 October 1911.

[80] “Memory of Dr. Timby to Be Honored

Tonight,” Washington (DC) Evening Star, 13 October 1911.

[81] Memorial ID 23639069,

Findagrave.com, accessed 4 November 2021.

[82] “John Brown’s Secret Motive,” The

New York Sun, 13 May 1904.

[83] “Veteran of Three Wars,” Milford

(IA) Mail, 5 October 1899.

|

Timby's Inventions

|

Date

|

Residence Given on Patent Application

|

|

Designed Floating Dry Dock (age 17), not patented |

1836 |

n/a |

|

US2572 Apparatus for Raising Sunken Vessels and Other Submerged

Bodies |

4/21/1842 |

Auburn, NY |

|

US2582 Machine for Dressing Stone |

4/23/1842 |

Auburn, NY |

|

US2613

Manner of Connecting the Body with the Runners of Sleighs |

5/7/1842 |

Auburn, NY |

|

Filed a Caveat with the US Patent Office for a Revolving Tower

for Land or Water |

1/18/1843 |

Cato, NY (Assumed) |

|

US3763 Improvement in Water-Wheels |

9/27/1844 |

Cato, NY |

|

US4845 Improvement in Water-Wheels |

11/10/1846 |

Cato Four Corners, NY |

|

US7464 Water Wheel - method for Increasing or Diminishing its

Diameter |

6/25/1850 |

Cato Four Corners, NY |

|

US7992 Removable Handle tor Sad-Irons |

3/18/1851 |

Meridian, NY |

|

US18560 Mercury Barometer |

11/3/1857 |

Medina, NY |

|

US21384 Traveling Casket |

8/31/1858 |

Medina, NY |

|

US35846 Improvement in revolving battery-towers |

7/8/1862 |

Worcester, MA |

|

US35847 Improvement in Discharging Guns in Revolving Towers by

Electricity |

7/8/1862 |

Worcester, MA |

|

US36593 Improvement in Revolving Battery-Towers |

9/30/1862 |

Worcester, MA |

|

US36871 Improvement in Portable Warming Apparatus |

11/4/1862 |

Worcester, MA |

|

US36872 Improvement in Mercurial Barometers |

11/4/1862 |

Worcester, MA |

|

US38193 Improvement in Solar Time-Globes |

7/7/1863 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

USRE1525 Improvement in Solar Time-Globes (re-issue ifUS38193 of

7/7/1863) |

8/18/1863 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

US40519 Improvement in Solar Time-Pieces |

11/3/1863 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

US47584 Improvement in Globe Time-Pieces |

5/2/1865 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

US47585 Improvement in Globe-Clocks |

5/2/1865 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

US62574 Improvement in Hoes |

3/5/1867 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

US65451 Ventilating Door (House Ventilator) |

6/4/1867 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

US73674 Paper-Cutter |

1/21/1868 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

US87445 Improved Railway Car-Wheel |

3/2/1869 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

US87446 Improved Case for Preserving Butter, Cheese |

3/2/1869 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

US90134 Improved Umbrella-Fastening |

5/18/1869 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

US90608 Improvement in Toilet Pin Cases |

5/25/1869 |

Saratoga Springs, NY |

|

US91580 Improvement in Turbine Water-Wheels |

6/22/1869 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

US93449 Improvement in Toilet Pin-Case |

8/10/1869 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

US96166 Improvement in Thimbles |

10/26/1869 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

US102622 Improvement in Sash-Fasteners |

5/3/1870 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

US102730 Improvement in combined Thread and Needle-Cases |

5/3/1870 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

USD4499 - (design patent) Design for a Medal |

11/29/1870 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

USD4622 - (design patent) Thread and Needle-Case |

1/31/1871 |

Town of Saratoga, NY |

|

US120552 Improvement in Railway Freight-Cars |

10/31/1871 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US120553 Improvement in Gun Carriages |

10/31/1871 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US121023 Improvement in Railroad Spikes |

11/14/1871 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US122682 Improvement in Construction at Railways |

1/9/1872 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

Timby's Inventions

|

Date

|

Residence Given on Patent Application

|

|

US122683 Improvement in Water-Meters |

1/9/1872 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

UA124174Improvement in Railway Rails |

2/27/1872 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US124175 Improvement in Railway Rails |

2/27/1872 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US131313 Improvement in Portable Wardrobes |

9/10/1872 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US135173 Improvement in Plant-Protectors |

1/21/1883 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US135386 Improvement in Car-Axle Lubricators |

1/28/1873 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US136284 Improvement in Springs for Vehicles |

2/25/1873 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US 136791 Improvement in Car-Axles |

3/11/1872 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US153691 Improvement in Cooking-Stoves |

8/4/1874 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US145258 Improvement in Railway Ties |

12/02/1873 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US171447 Improvement in Spikes |

12/21/1875 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US171448 Improvement in Spikes |

12/21/1875 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US168809 Improvement in Attachments for Cooking-Stoves |

10/11/1875 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US172798 Improvement in Attachments for Cooking-Stoves |

1/25/1876 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US181224 Improvement in Cooking-Stove Attachments |

8/15/1876 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US173690 Improvement in Attachments for Cooking-Stoves |

2/15/1876 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US173691 Improvement in Attachments for Cooking-Stoves |

2/15/1876 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US180962 Improvement in Apparatus for Manufacturing Solar Salt |

8/6/1876 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US198435 Improvements in Salt-Cellars and Napkin-Holders |

12/18/1877 |

Tarrytown, NY |

|

US217754 Improvement in Ore and Rock Crushers |

7/22/1879 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US224492 Cooking-Vessel |

2/10/1880 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US225665 Ore-Crusher |

3/16/1881 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US246345 Ore Separating & Amalgamating Machine |

8/23/1881 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US239203 Coast Defense |

3/22/1881 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US239202 Coast Defense |

3/22/1881 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US240786 Coast Defense |

4/26/1881 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US243007 Car-Axle |

6/14/1881 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US246987 Subterranean System of Coast Defense |

9/13/1881 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US273913, Steam Cooker |

3/13/1883 |

Brooklyn, NY |

|

US281651 Combined Amalgamator & Separator |

7/17/1883 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US296251 Apparatus for Treating Ores |

4/1/1884 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US312230 Tower & Shield System of Fortification |

2/10/1885 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US312231 System of Firing Battery Guns in Turrets by Electricity

|

2/10/1885 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US312232. Revolving Tower and Shield System of Fortifications |

2/10/1885 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US330642 Revolving Tower System of Fortifications |

11/17/1885 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US330638 Revolving Tower System of Fortifications |

11/17/1885 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US330639 Revolving Tower System of Fortifications |

11/17/1885 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US330640 Revolving Tower Fortifications |

11/17/1885 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US330641 Revolving Tower System of Fortifications |

11/17/1885 |

Nyack, NY |

|

US344758 Gun Carriage for Revolving Turrets |

6/29/1886 |

Washington, DC |

|

US379744 Heat and Power Supply System |

3/20/1888 |

Washington, DC |

|

US465298 Apparatus for Heating, Cooling, and Ventilating |

12/15/1891 |

Washington, DC |

|

US418581

Revolving-Tower Fortification |

10/22/1889 |

Washington, DC |

|

US413582 Sighting Platform for Revolving Turrets |

10/22/1889 |

Washington, DC |

|

Timby's Inventions

|

Date

|

Residence Given on Patent Application

|

|

UA462602 Process of Purifying Iron and Steel |

11/3/1891 |

Washington, DC |

|

US475637 Apparatus for Evaporating Brine |

5/24/1892 |

Washington, DC |

|

US474271 Revolving-Tower Fortification |

5/3/1892 |

Washington, DC |

|

US485999 Process of and Apparatus for Aging Liquors |

11/8/1892 |

Washington, DC |

|

US486000 Apparatus for Aging Wines, Spirits, or Other Liquors |

11/8/1892 |

Washington, DC |

|

US496759 Process of and Apparatus for Aging Wines |

5/2/1893 |

Washington, DC |

|

US527564 Apparatus for Aging Wines or Distilled Liquors |

10/16/1894 |

Washington, DC |

|

US660602 Method of Ripening Coffee |

10/30/1900 |

New York, NY |

|

US673227 Apparatus for Seasoning Coffee |

4/30/1901 |

New York, NY |

|

US754943 Method of Roasting Coffee |

3/15/1904 |

Brooklyn, NY |

|

US749340 Coffee-Treating Machine |

1/12/1904 |

Brooklyn, NY |

|

US741389 Mechanism for Utilizing Wind-Power |

10/13/1903 |

Brooklyn, NY |

|

US769330 Machine for Aging Liquors |

9/6/1904 |

Brooklyn, NY |

|

US777569 Car-Wheel Axle |

12/13/1904 |

Brooklyn, NY |

|

US779978 Water-Wheel |

1/10/1905 |

Brooklyn, NY |

|

US857317 Lines for Vessels |

6/18/1907 |

Brooklyn, NY |